Twenty years after the release of the first "Harry Potter" movie and ahead of the Jan. 1 reunion special on HBO Max, questions like "What Harry Potter house am I?" still garner thousands of search hits every day. Over the past 12 months, that term and similar ones were Googled an average of 82,700 times a month in the U.S. For comparison, the same metrics for "Harry Potter cast now" and "J.K. Rowling transphobic" are 5,400 and 12,100 respectively.

I'll admit I cried on the evening of my 11th birthday when I didn't get a letter inviting me to attend Hogwarts. But it wasn't the realization that I'd never do magic that pushed me over the edge. It was never donning the sorting hat and confirming that I'm a Ravenclaw. I'd often imagined the hat telling me who I am and what I stand for, useful information in Harry's world and my own.

"What the sorting hat does is allow you to fantasize in your own particular way," English professor Neil Randall, who created a popular course about "Harry Potter" at University of Waterloo in Canada, told me. "You get to pick the way you're going to read the story and who you're going to sympathize with. ... It's hard not to become part of it and wonder what the other possibilities might be."

Fantasy characters, real friends

What keeps us wondering about our own lives at Hogwarts even when we know we'll never get the chance to go there? It's the characters, who drive the stories more than those in other fantasy books, like the "Lord of the Rings" series, Randall theorized. "When you think of 'Harry Potter,' you think of the three main characters, and then there's your favorite other characters, whoever they happen to be."

Hearing this was like someone casting "lumos" in my head. Reading the books, I was the invisible fourth leg of the beloved tripod, and I needed to know which house I'd be in to invent my little subplots about how I became friends with them.

"People reading the books when they were young are thinking, 'They're the same as us, except that they have magic,'" Randall said.

The way the characters behave is so believable that Georgene Troseth, a professor at Vanderbilt University, uses "Harry Potter" as a framework for an introductory developmental psychology course that she's been teaching for over a decade.

"When I began to read the books with my youngest son ... I kept putting notes in the margins, 'Great example of friendships,' or 'This is really wonderful about attachment,'" she recalled. "It just seemed like J.K. Rowling had a good instinct for a lot of information about child development that she incorporated into her novels."

"The books that endure tend to have real psychology underlying dragons and the space aliens," Troseth said. "Otherwise, it just seems artificial and trivial."

Healing through nostalgia

Revisiting old stories and happy parts of our past can be especially powerful when we're going through trauma, like a persistent pandemic. And the late-2001 release of the first movie means the national consciousness already associates Harry Potter with another world-changing event, Randall said.

"It's a healing balm in a way ... grasping onto something. The Potter fantasy world made more sense than the one that people were living in at the time."

The generation that grew up as the books were released from 1998 to 2007 is also known for clinging to childhood relics. We're Disney adults, lust after Lisa Frank and have been dragged by Gen Z for defining ourselves as Hufflepuffs, Gryffindors, Ravenclaws and Slytherins.

"Anybody who came through it and was of a certain age is not likely to forget it, and not likely to put it aside, so you're going to go back and look again at what those things brought you and it becomes fun," Randall said. "[It's] like looking through your closet and seeing your old T-shirts."

Nostalgic fandoms have also flourished online, extending the life of the central subject. "People who have a hard time making friends or are shy, the internet can really help because it's easier to find people that have your same interests," Troseth said.

Myers-Briggs, astrology and first date fodder

In the world of psychology outside "Harry Potter," Lehigh University professor Dominic Packer, co-author of "The Power of Us," reaffirmed what I've always thought: The houses speak to innate human desires. He said his research shows that people form positive associations with groups they're part of, even when the group doesn't have any meaning and they don't know anyone else within it.

"It suggests people have this readiness to affiliate with others in some sort of category that makes us distinct," Packer explained. "We want to believe ... we're part of a group and we're good, maybe better than others, and we're also different."

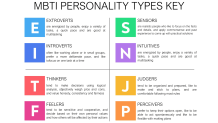

Packer compared Harry Potter house quizzes to the popularity of the Myers-Briggs personality test, which focuses on four categories: introversion or extraversion, sensing or intuition, thinking or feeling, judging or perceiving.

"[The test] says, 'You're this. We're going to put you in a category and give you a label.' By doing that, people can resonate to it and make sense of it. .. It's more satisfying than saying, 'Well, I'm a bit high in conscientiousness and kind of low on extraversion,' which doesn't sound nearly as cool. You can't talk about it on a first date or or put it on your Facebook profile," Packer said, adding that astrology for some people satisfies a similar urge.

I wondered if the fact that Harry got to choose which house he was put in made Packer's research less applicable, but not so.

"We're part of all sorts of groups and categories in real life, and it can feel sort of inevitable, like that's just who I am," he said. "But some of our identities, we have control over. You can decide, 'Which house do I want to be part of? What kind of person do I want to be?' That's actually a really important side of the equation."

For those of us who read the books as kids, being presented with that agency at a young age may contribute to the lasting power of the houses, too.

"A lot of the things that people encounter during ... adolescence especially turn out to be very meaningful things throughout their lives," Packer said. "On average, people have a better memory for things from their teen years than from any other point in their lives."

Finding your place — again

For several years, former sociology professor Bertena Varney got to introduce students from a range of backgrounds to the "Harry Potter" houses through her course at Southern Kentucky Community and Technological College, which used the series to teach about inequality in society. She started the semester with her version of the sorting hat, asking students "to delve into who you really think you are," she said.

Because the house personas convey both strengths and flaws, it evolved into an opportunity to ponder personal growth, as well. She recalled joking with her students that she's a Ravenclaw, which means she should strive to be more patient with people less interested in learning than she is.

"We cling to Hogwarts houses [because] they really let us know who we are, what we enjoy ... and where we need to better ourselves," she explained.

Varney doesn't think it's a coincidence that so many of her students, who learn to identify with the houses, go on to social service roles.

"They saw the good that they could do," she said. "They all go back to this [idea of] 'Harry Potter help me love myself and then learn how to love other people.'"

The impulse to return to the series isn't unique to Varney's students, of course. I watch all eight movies every winter while mulling over the insights I gleaned from "Binge Mode: Harry Potter," my favorite podcast. Since turning 11, I've become confident in my identity as a Ravenclaw, but I've still revisited the quiz without thinking that hard about why. Magically, Varney has a theory.

"The sorting hat is what made you part of 'Harry Potter,'" she told me. "If you feel like you're lost in this world, you go back to Hogwarts to the sorting ceremony to find your place again."